I have heard what the talkers were talking, the talk of the beginning and the end;

But I do not talk of the beginning or the end.

There was never any more inception than there is now,

Nor any more youth or age than there is now;

And will never be any more perfection than there is now,

Nor any more heaven or hell than there is now.

Urge, and urge, and urge;

Always the procreant urge of the world.

Out of the dimness opposite equals advance . . .

Walt Whitman, a Kosmos, of mighty Manhattan the son

Tuesday, August 28, 2007

Sunday, August 12, 2007

A snake whose scales are tiny mirrors in which the dead world takes on a semblance of life

As a boy in his father's church, he had discovered that something stirred in him when he shouted the name of Christ, something secret and enormously powerful. He had played with this thing, but had never allowed it to come alive.

He knew now what this thing was--hysteria, a snake whose scales are tiny mirrors in which the dead world takes on a semblance of life. And how dead the world is . . . a world of doorknobs. He wondered if hysteria were really too steep a price to pay for bringing it to life.

Nathaniel West, Miss Lonelyhearts

He knew now what this thing was--hysteria, a snake whose scales are tiny mirrors in which the dead world takes on a semblance of life. And how dead the world is . . . a world of doorknobs. He wondered if hysteria were really too steep a price to pay for bringing it to life.

Nathaniel West, Miss Lonelyhearts

Saturday, August 4, 2007

A cutting retort you have never forgotten

A small boy you come out of Connolly's Stores holding your mother by the hand. You turn right and advance in silence southward along the highway. After some hundred paces you head inland and broach the long steep homeward. You make ground in silence hand in hand through the warm still summer air. It is late afternoon and after some hundred paces the sun appears above the crest of the rise. Looking up at the blue sky and then at your mother's face you break the silence asking her if it is not in reality much more distant than it appears. The sky that is. The blue sky. Receiving no answer you mentally reframe your question and some hundred paces later look up at her again and ask her if it does not appear much less distant than in reality it is. For some reason you could never fathom this question must have angered her exceedingly. For she shook off your little hand and made you a cutting retort you have never forgotten.

A small boy you come out of Connolly's Stores holding your mother by the hand. You turn right and advance in silence southward along the highway. After some hundred paces you head inland and broach the long steep homeward. You make ground in silence hand in hand through the warm still summer air. It is late afternoon and after some hundred paces the sun appears above the crest of the rise. Looking up at the blue sky and then at your mother's face you break the silence asking her if it is not in reality much more distant than it appears. The sky that is. The blue sky. Receiving no answer you mentally reframe your question and some hundred paces later look up at her again and ask her if it does not appear much less distant than in reality it is. For some reason you could never fathom this question must have angered her exceedingly. For she shook off your little hand and made you a cutting retort you have never forgotten.Samuel Beckett, Company

Thursday, August 2, 2007

If You Only Knew

Far from me and like the stars, the sea and all the trappings of poetic myth,

Far from me but here all the same without your knowing,

Far from me and even more silent because I imagine you endlessly.

Far from me, my lovely mirage and eternal dream, you cannot know.

If you only knew.

Far from me and even farther yet from being unaware of me and still unaware.

Far from me because you undoubtedly do not love me or, what amounts to the same thing, that I doubt you do.

Far from me because you consciously ignore my passionate desires.

Far from me because you are cruel.

If you only knew.

Far from me, joyful as a flower dancing in the river at the tip of its aquatic stem, sad as seven p.m. in a mushroom bed.

Far from me yet silent in my presence and still joyful like a stork-shaped hour falling from on high.

Far from me at the moment when the stills are singing, at the moment when the silent and loud sea curls up on its white pillows.

If you only knew.

Far from me, o my ever-present torment, far from me in the magnificent noise of oyster shells crushed by a night owl passing a restaurant at first light.

If you only knew.

Far from me, willed, physical mirage.

Far from me there's an island that turns aside when ships pass.

Far from me a calm herd of cattle takes the wrong path, pulls up stubbornly at the edge of a steep cliff, far from me, cruel woman.

Far from me, a shooting star falls into the poet's nightly bottle.

He corks it right away and from then on watches the star enclosed in the glass, the constellations born on its walls, far from me, you are so far from me.

If you only knew.

Far from me a house has just been built.

A bricklayer in white coveralls at the top of the scaffolding sings a very sad little song and, suddenly, in the tray full of mortar, the future of the house appears: lovers' kisses and double suicides nakedness in the bedrooms strange beautiful women and their midnight dreams, voluptuous secrets caught in the act by the parquet floors.

Far from me,

If you only knew.

If you only knew how I love you and, though you do not love me, how happy I am, how strong and proud I am, with your image in my mind,

to leave the universe.

How happy I am to die for it.

If you only knew how the world has yielded to me.

And you, beautiful unyielding woman, how you too are my prisoner.

O you, far-from-me, who I yield to.

If you only knew.

Robert Desnos

Far from me but here all the same without your knowing,

Far from me and even more silent because I imagine you endlessly.

Far from me, my lovely mirage and eternal dream, you cannot know.

If you only knew.

Far from me and even farther yet from being unaware of me and still unaware.

Far from me because you undoubtedly do not love me or, what amounts to the same thing, that I doubt you do.

Far from me because you consciously ignore my passionate desires.

Far from me because you are cruel.

If you only knew.

Far from me, joyful as a flower dancing in the river at the tip of its aquatic stem, sad as seven p.m. in a mushroom bed.

Far from me yet silent in my presence and still joyful like a stork-shaped hour falling from on high.

Far from me at the moment when the stills are singing, at the moment when the silent and loud sea curls up on its white pillows.

If you only knew.

Far from me, o my ever-present torment, far from me in the magnificent noise of oyster shells crushed by a night owl passing a restaurant at first light.

If you only knew.

Far from me, willed, physical mirage.

Far from me there's an island that turns aside when ships pass.

Far from me a calm herd of cattle takes the wrong path, pulls up stubbornly at the edge of a steep cliff, far from me, cruel woman.

Far from me, a shooting star falls into the poet's nightly bottle.

He corks it right away and from then on watches the star enclosed in the glass, the constellations born on its walls, far from me, you are so far from me.

If you only knew.

Far from me a house has just been built.

A bricklayer in white coveralls at the top of the scaffolding sings a very sad little song and, suddenly, in the tray full of mortar, the future of the house appears: lovers' kisses and double suicides nakedness in the bedrooms strange beautiful women and their midnight dreams, voluptuous secrets caught in the act by the parquet floors.

Far from me,

If you only knew.

If you only knew how I love you and, though you do not love me, how happy I am, how strong and proud I am, with your image in my mind,

to leave the universe.

How happy I am to die for it.

If you only knew how the world has yielded to me.

And you, beautiful unyielding woman, how you too are my prisoner.

O you, far-from-me, who I yield to.

If you only knew.

Robert Desnos

It was a cross. She saw it as a cross, and it made her feel, right or wrong, that there was an element of forgiveness in the picture, that the two men and the woman, terrorists, and Ulrike before them, terrorist, were not beyond forgiveness.

Don DeLillo, "Baader-Meinhof"

from The New Yorker, April 1, 2002

each individual must foment a private conspiracy

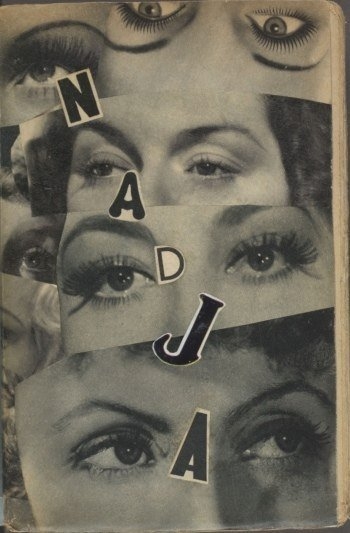

But Nadja was poor, which in our time is enough to condemn her, once she decided not to behave entirely according to the imbecile code of good sense and good manners. She was also alone: "At times, it is terrible to be so alone. I have no friends but you," she said to my wife on the telephone, the last time. She was, finally, strong, and extremely weak, as one can be, in that idea she had always had but in which I had only too warmly encouraged her, which I had only too readily aided her in giving supremacy over all the rest: the idea that freedom, acquired here on earth at the price of a thousand--and the most difficult--renunciations, must be enjoyed as unrestrictedly as it is granted, without pragmatic considerations of any sort, and this because human emancipation--conceived finally in its simplest revolutionary form, which is no less than human emancipation in every respect, by which I mean according to the means at every man's disposal--remains the only cause worth serving. Nadja was born to serve it, if only by demonstrating that around himself each individual must foment a private conspiracy, which exists not only in his imagination--of which, it would be best, from the standpoint of knowledge alone, to take account--but also--and much more dangerously--by thrusting one's head, then an arm, out of the jail--thus shattered--of logic, that is, out of the most hateful of prisons.

Andre Breton, Nadja, pp. 142-143

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)